Bestiary |

Rulers of the Slavic pantheon

Although very little information about them has survived, the Slavic gods are quite popular. Thanks to revivalists, tireless collectors of folklore, archaeologists. We will not deal with the analysis of sources, nor with the quite interesting relations of Slavic paganism to the beliefs of neighboring nations. On the agenda is merely an introduction to the royalty to which the whole Slavic world once bowed.

Svarog

Apparently, this ancient god of fire and celestial light, the divine smith, was one of the oldest, if not the oldest god, which usually carries with it a demiurgic function. He also legislated, among other things, the abolition of polygamy, which offenses were punished in the future by burning the offenders in the furnace.

The name of Svarog is a reminder of the common Indo-European roots of European civilization, the weld in that ancient language has the meaning of light. As Creator God, he also shares a fate common to many other demiurges, stepping aside after the work is done to make way for younger ones. He is not worshipped, only remembered.

Svarozhits – Dazhbog

By name alone, he is the son of Svarog, the god of the second generation. Thanks to his father's functions, he became - like the descendants of similar deities among other nations - a solar god, the giver of life and overseer of what his father created and invented. He was worshipped at solstices and equinoxes, and his earthly embodiment was fire.

While his father Svarog enjoyed retirement, Svarozhits occupied much divine space, and like Greek deities, for example, he had a number of epithets that later became separate names by which the son of Svarog was known in various parts of Slavic Europe. In the east Dažbog, in the south Dabog, both names are based on dažd - to give, but quite possibly there is also a connection with the Indo-European dag, meaning to burn, in which case again the solar function of Svarogic would be alluded to. Zdeněk Váňa cautiously suggests a possible connection with the British god of fire Dagbra.

In the West Slavic world, Svarozhits was later – and probably under local influence – renamed Radegast, but we will talk about this sir another time.

Perun

The most famous of the Slavic global deities. Although not listed here in the first place, he was the supreme deity. Understandably entrusted with rule over thunder, lightning, and storms.

Most of the information, however, comes from the East, especially thanks to Prince Vladimir. The Kyiv ruler decided to strengthen the power of the state with an officially sanctioned religion. For several years it looked as if the time-honored pagan path would continue, but Christianity proved a more viable option, so Vladimir did not hesitate to destroy the newfangled luxury idols. But in the meantime, he respectfully sacrificed them and, according to a verified source, humans. The old Slavic sacrifices, by the way, were not for the delicate natures. Their essence was the blood that flowed down the altar, whose vapors attracted beings from beyond the grave, making them visible and capable of securing communication between the two worlds. This practice is known from all over the world, and the Slavs did not shy away from it, as well as the sacrifice of captives. But to appeal to those with more sensitive stomachs, non-bloody libations (alcoholic beverages were used more than milk) and food offerings, cheese, honey, bread, or grain, were just as common.

The Perun tree is the oak, the most sacred of trees in the entire Indo-European world. As an aside, the worship of the linden tree, the tree that became our (i.e. Czech) national tree, is only attested in modern times; the ancient cult of the linden tree is only conjecture, derived from the rather widespread cult of the Virgin Mary associated with this tree, and also because of certain magical practices and information associated with the linden tree from time immemorial.

The day of the week dedicated to Perun is, quite unoriginally, Thursday, when many thunder potentates, such as the Norse Thor or the Roman Jupiter, enjoy. And his attribute is the axe. Not the tool of the peaceful woodcutter, but (like the hammer of Mjöllni Perun's Germanic colleague Thor) the war axe, the standard armament of the Slavic warrior. Amulets in its form have been found in many mounds.

Predominantly a war god, Perun became the head of Vladimir's pantheon. But after only eight years his idol ended up in the Dnieper, and the axe was replaced by a cross.

Veles or Volos

Federal Minister of Agriculture, also a protector of property. Under these functions was the original god of fertility. According to some indications, a god of the underworld. This is not excluded, although there is no direct evidence of it: vegetation deities with their annual cycle often flirted with the realm of the dead, and the spring-summer-winter circle leads directly to this.

After the Christian upheaval, Veles, like his divine contemporaries, became a demon. This was not merely expedient; the horned appearance of the protector of flocks and the phallic symbols of the fertility god predisposed him, like the Greek Pan, to a similar degeneration. His name became synonymous with the devil.

Well, that's about it. I admit that it was a really cursory performance and not worthy of the gentlemen mentioned, but certainly not exhaustive. But don't despair, next time there will be deities of lesser geographical importance (though names of quite familiar importance), and I will say even less about them.

Picture of Svarog by Andrey Shishkin, CC BY 3.0-2.5-2.0 1.0, via Wikimedia Commons

11.4. 2025 (2.10.2004)

Rulers of the Slavic Pantheon 2 – In Kyivan Rus

Late Slavic paganism was concentrated in two areas. The first was Kyivan Rus, and the second, quite successful, was the region around the Elbe River in what is now northern Germany. While elsewhere Christianity was gaining ground and sending the old gods into retirement and oblivion, in those enclaves the pagan faith survived long enough to see the age of the written word. Thus we know nothing more about the gods worshipped here in Bohemia than that they were worshipped, all names dating from much later times. From the Czech National revival times, and also from the rich imagination of Václav Hájek from Libočany.

It was better in the East.

But let's take it one step at a time.

At the end of the tenth century, Prince Vladimir decided to nationalize the faith and turn it into a political tool. In addition to the generally revered divine authorities belonging to the entire Slavic world, four more names appeared in the Kyiv pantheon.

Stribog

According to certain indications, his grandsons were the personification of the winds, and Stribog himself was either the Steward of Good, according to the name derived from the stroj, or the opposite of Dazbog, and thus the Remover of Good, which is suggested by The Tale of Ihor's Campaign and to which the ethnographer J. Schütz inclines. In fact, all information about Stribog's function is based only on the interpretation of his name, since all the original sources only mention this god.

Chors (Khors)

A name often mentioned in ancient sources, supplementing the list of much better-known gods. It is usually associated with the Sun or the Moon, based on only one passage from The Tale of Ihor's Campaign, where Prince Viseslav in wolf form crossed Chors' path. An etymological theory, interpreting Chors' name from the Iranian chorsid, the shining sun, argues for a solar deity. A minor but not insignificant lunar branch is then represented from the same perspective by the view that the name originated from the Old Slavic krs, emaciated. Nor is Chors' function anywhere explained,

Simargl

A deity even more unknowable than the preceding two. Here and there it is supposed to be two gods, Sim and Rgl. His name is also interpreted in connection with the seven-headed god; the Slavs did have such deities, but not in the East. According to Zdeněk Váňa, two interpretations are relevant. The first one is offered even to a layman who is only slightly familiar with the old mythology - the Persians, or Iranians, whose influence on Slavic religion was not negligible, knew the Simurgh, a monster with the body of a bird, the head of a dog and the paws of a lion. It is the direct influence of one culture on another that precludes the inferior mythological being of one from becoming the god of the other. Therefore, the second version, the one that allows for a divine pair, comes into play. The first part of it - Sim would represent the protector of cattle, Rgl the protector of grain - is suggested by the possible origins of the names from the Proto-Slavic words sěma (family) or sěme (seed) on the one hand and rž (rye, grain) on the other. The Slavs would then not have missed the quite common Indo-European figure of Gemini.

Mokoš

The only goddess in an otherwise male-dominated society. Her worship is attested as far back as the sixteenth century; the folkloric big-headed and long-armed Mokusa of the Ukrainians, who is her descendant, is the protector of sheep and spinning, who walks around the cottages at night spinning her skein.

Mokoš was the goddess of the earth, and this function is of course associated with a fertility cult and certain sexual mysteries, appropriate to her professional colleagues, such as the Greek Demeter or, much closer to Mokoš, the Iranian Ardvi Sura or Anāhitā, goddess of moisture, crops and fertility. It was the surname Ardhví (meaning moist) that may have given Mokoš her name in Slavic translation.

Trojan

Was he a god or just a demon? And wasn't he just some mythical figure of an ancient king after all? Occasionally, though, scholars lean toward the most understandable (but otherwise somewhat illogical) deification of the Roman emperor Trajan. He did indeed make a campaign as far as Dacia but to his detriment half a millennium before the Slavs moved in. He probably entered the lists as Heracles numbered among the Olympian gods, a former tribal leader or king so famous that he was declared a saint.

25.4.2025 (11.10.2004)

Rulers of the Slavic Pantheon 3 – Once Upon a Time in the West

For the third and last time, we will stop by the old Slavic gods. This time in the West, as the title reveals.

I won't go into the reasons why the westernmost outpost of Slavic settlement held on to pagan beliefs until the twelfth century. Others, more educated, had already done that. Let us rather bow to the gods for whom we are here today in the Bestiary.

Radogost

A name still common in Bohemia, Lusatia, and Lower Austria. But here these are local names, while Radegast – the god was a local variant of Svarožič. As in many other cases, the later name is originally just an acronym – from Svarožič "He Who Welcomes Guests", over time it became just "He Who Welcomes Guests".(Sometimes it is the other way around and the god imports a god of another cultural area into his name, for example, Zeus Ammon and many others).

Or else. From the beginning of the eleventh century there is a description of the Ratara temple, where, among others, Svarožič is the foremost of the gods. Worshipped, unfortunately, by human sacrifices. The temple was located, let's see, in a castle called Radegost.

The shrine lived by divination, the most common practice being the walking of a sacred horse over crossed spears. The most common request from clients was to inquire about the success of a war campaign. If the horse crossed the spear with its right foot, it was good. Thus the constable Radogost was gradually becoming a universal god from a sun god, his former profession being recalled only by the boar, sometimes visiting the mud by the lake surrounding the castle. It, too, foretold the coming wars but was originally an animal of the solar cult.

Svantovit

Today, his once magnificent temple is underwater, having had to give way to the wild Baltic Sea, which has bitten its share of the former peninsula of Rügen. Svantovit is by no means a de-Christianized version of St. Vitus, whether brought to Rügen by Corwey monks or bought by the Lutici in Prague, where Prince Wenceslas had a temple built to this Saint. The Slavic svet used to mean mighty and -vit is a victor. Just like the Radegast of Rana, Svantovit was originally an attribute, but in this case, it is not clear which god.

In any case, it was a powerful enough one, because Svantovit was sacrificed not only by the Lutici but also by the surrounding tribes and in some cases by the Scandinavian Vikings, to whom the Slavic pirates of the Baltic were more than a match. Even the Danish king Sven dared for once to forgive his native faith and redeem himself in a Rügen sanctuary, but here it was a matter of politics, with the warlike Slavic neighbors he could then count on in the internal settlement of his own state.

As a powerful local deity of later times, Svantovit already combined the main divine functions, namely economic and warfare. The horse and crossed spears were used for divination here too – this was when military or naval prognostication was involved, but also the great drinking horn and the honey cake, which were used for agrarian predictions.

Triglav

In ancient times, famous trading ports were built at the mouth of the Oder River. Until the twelfth century, the largest was Wolin, also known in the surrounding world as Vineta or Jómsburg. Szczecin grew up next to it (until it outgrew it).

Both ports were ruled by a god who - here we go again – may be known by his former nickname. Indeed, Triglav – Three-Headed – may very well come from the description of his idols, namely the three-headed or three-faced statues of Szczecin and Wolyn. It was certainly not an echo of the Christian Holy Trinity (which is only rarely depicted as three-headed, and only since the thirteenth century). In fact, the superimposition of heads probably belonged to the Western Slavic faith; in Rügen, besides the aforementioned Svantovit, the lower-statured but seven-faced Rugievit was also worshipped, while Porenutius from the same region had four faces, the fifth on his chest.

The practices of the cult were the same, with a horse dedicated to Triglav, who also divined by crossing a spear.

25.4.2025 (17.10.2004)

Bejválek

Back to the supernatural plebs after the visit to the honorarium. Or to the middle class, because although Bejválek is like a little boy with a big head looking elf, he holds the responsible position of guardian spirit of the Bohemian Forest foothills, the area between Nepomuk and Plánice. Like most guardian spirits he is quite good-natured, but he can get quite angry when provoked.

(24.10.2004)

Klepacek

The ghost of one of the mayors of the Central Bohemian town of Beroun. He announces his arrival by knocking on the wall, hence the present name. It is somewhat reminiscent of the ghosts of the mines, perhaps that is why later folk tradition attributed to him a hood and a hammer, but it was generally believed that he was a conscientious town official who, even under torture, did not reveal where he had hidden the town's treasures, so after his death he became the supernatural guardian of them. I don't know how it is with the Beroun municipal treasury today, but once Klepáček drove a dishonest scribe to suicide by poltergeist practices that are his own (i.e. knocking on doors, throwing various objects, and opening doors).

25.4.2025 (24.10.2004)

Red Cap

I haven't encountered anything this dangerous in a long time. Fortunately, it only happened on my son's Gameboy in the Potter games, and there the collision with Red Cap was manageable. In the creature's actual habitat, however, I would be scared. Very scared.

He gets his name Red Cap from an unmissable item of clothing, a hat (or Scottish beret) of red, but don't expect the bright red to be the result of the textile industry's factory dyes; in fact, this small, elderly-looking creature with long grey hair likes to dip his headgear in the blood of his victims. Into the leftover blood that he doesn't finish drinking. That information alone is alarming, and what's more when you realize that the dried blood is dark brown, and we're not dealing with any Brown Cap. The color must be fresh!

But enough scaremongering, it's time for more concrete information. The Red Cap is a supernatural inhabitant of old castles and watchtowers in the Scottish Borders, and his favorite places are those of bloody history. In addition to the aforementioned headgear, he also wears iron boots, despite being very fast. If he's not killing with his long, sharp claws, then he resorts to ambush attacks: hurling boulders at unsuspecting victims. In such a case, even biblical quotations, which, if attacked directly, can drive Red Cap away, are of no help.

(6.11.2004)

Vitore

A small snake living in the walls can be an unwelcome lodger or a cheerfully welcomed protective spirit of a home or family. The Albanian Vitore belongs, of course, to the latter group. He announces joyful events with a low whistle, which is quite classy. Unfortunately, he also uses the same vocal expression to announce future things of the opposite polarity, i.e. miserable.

25.4.2025 (6.11.2004)

Liekkiö

This little creature walks through the Finnish forests at night. With a lantern in its hand, more precisely with some unspecified light source, it is a Finnish Will-o'-the-wisp. In keeping with many other European traditions, it is the soul of a child, in this case, a child buried in the forest, whose spirit has become the protector of wildlife and trees.

25.4.2025 (6.11.2004)

Duwende

If something is rustling in the walls of a European apartment or tossing objects, then it is most likely a poltergeist. Or a very cheeky mouse. If something chirps and rattles in a Filipino house, it's probably a duwende. This mostly friendly creature looks like an undersized old man, it's no more than three feet tall (or much less, depending on what story you want to cast it in), and even he manifests by throwing sand and rocks in addition to sound. Sometimes considered a Filipino form of dwarf, he lives underground and doesn't have deep pockets, for like any proper demon of this element he has a considerable amount of gold.

A final safety note: the aforementioned domestic form of duwende sometimes spreads disease, even deadly disease.

25.4.2025 (14.11.2004)

Aitu

They appear in Polynesia in the form of animals or plants. However, they belong to the family, they are the souls of the ancestors who, as has become customary in the wide world, look after the descendants. In the Marquesas they are called atua, they live in trees and fly like birds.

25.4.2025 (14.11.2004)

Yu-qiang

Chinese sea god and also head of the ocean winds department. He performs the first function in the form of a fish and his service vehicle is two dragons (Chinese, i.e. positive), for the second office he chose to metamorphose into a bird-like creature, the face of a human.

25.4.2025 (14.11.2004)

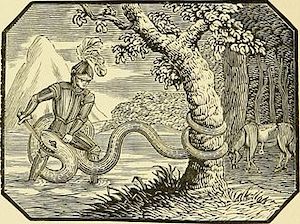

Lambton Worm

The Lambton Worm, or dragon, in older English the word worm had the same content, is the most famous of Britain's dragon creatures. And you know what? Listen to the whole story.

It was one Sunday when young Lambton went to the River Wear to fish while everyone else dutifully walked to mass in Brugeford. God is watching, and that's probably why staring at the float was a complete waste of time. At least for a few long hours; it worked after all. The heir to the Lambton estate hooked and pulled and pulled, it looked like a really capital catch, only then something that looked nothing like a fish appears at the end of the rod.

It was a big black worm with a newt's head and sharp needle-like teeth. Young John naturally wanted to throw the apparently inedible catch back, but where it came from, there it came, a strange old man appeared beside him.

"I wouldn't put it back in the water. Looks like you caught the devil himself."

He added some more of that fairy-tale wisdom and disappeared again.

Young Lambton shrugged his shoulders, put the worm in the basket, and threw it into the old well on his way home. It's been called Worms Well ever since.

Time passed and the reckless Lambton heir became a man aware of his origins and his responsibilities. So he set out with the king for the Holy Land.

Meanwhile, the Worm grew. The water in the well became poison by its presence, poisonous vapors issued from it, and unsuspecting country folk began to talk of the strange curse that had befallen the old spring. They did not know why the well had been poisoned, or what was actually living in it, until the next morning, when they discovered that a black slug's trail stretched from the well to the river. But when the worm emerged that night in full dragon strength, it was clear that it was no good.

The monster crawled to the river, slipped into the water, and swam to a small rocky island in the current, circled around it three times, and displayed its beauty to the public. The dragon had neither wings nor legs; it still looked like a huge ugly worm, strong and muscular. For some time it did nothing, but then the dark expectations were fulfilled, and the time of the first sacrifice came.

With one swallow, the creature could devour a small lamb. It scared cattle and chewed through cows' udders to get at the milk. The local agriculture-based economy began to collapse. And it was getting worse.

So a few brave men set out to slay the dragon. Those who drowned before reaching the island at least escaped the horrible death of their comrades, who were torn apart by the worm. And, horror of horrors, the battle-torn dragon eventually made its way to Lambton Hall.

Fortunately, the castle was ready for him. They filled a large stone trough with boiling milk, set it in the courtyard, and waited to see if the worm would accept the bribe. The dragon crawled to the gate, paused, and because his throat got really dry on the way, it actually bent down to the trough and drank the milk. Whereupon it returned contentedly to the river. The next day, however, comes again, and the next day also. Every day for seven years the dragon crawled to the castle, drank his dose of hot milk, and returned without attacking anyone or biting any of the cattle. Life in the village was slowly returning to its old ways. Every now and then, though, someone tried to kill the dragon, but no knight or dragon slayer defeated the monster, never resulting in anything other than the death of the brave challenger. The villagers had to get used to the daily milk tax.

When John Lambton returned from the Crusades seven years later, he was astonished. He had quite forgotten his former catch; he had other things to do in the Holy Land. He had not expected a fortnight of celebration and festivities, but he certainly had not thought it would be like this at home. The economy of the land was in ruins, his father over the grave. A monster in the river feared throughout the North. What to do about it?

Because John was not only grown and battle-hardened but also rational, he didn't draw his sword and lunge straight at the dragon like the ragged ones had done. Instead, he visited the Brugeford Witch.

“Of course, it's your fault,” she told him at the door, "you should have gone to mass on Sunday, not fishing. That's what it looks like when one forgets one's faith. Some brawl with the Saracens won't save it."

The Lambton heir humbly listened to the witch's ramblings, the information that only he could kill the dragon, and above all, the important technical advice: Have a blacksmith make him a suit of armor covered with sharp thorns. By doing so, the worm loses the advantage of one of his weapons - namely, the grip of his opponent in a deadly hug. It was not a foolish idea at all, which the future Sir Lambton recognized, not knowing that he would be using the most ancient and, after calfskin stuffed with quicklime, the most common method of destroying dragons, known in Greece, France, Spain and even in distant and yet undiscovered China.

He rose to go, but the witch stopped him,

"Wait a moment. Anyone could have told you that trick with the armor, you didn't have to go to the old woman for that. There's a catch to the whole thing."

“And what is that?” asked the Lambton heir, his hand on his wallet and a little uncertainty in his voice.

“If you kill the worm - it is nowhere written that you must succeed - then you must also kill the first one who crosses your path when you step over the threshold of Lambton Hall.”

“Why would I do that?”

“Because if you don't, a curse will befall your clan and three times three generations of Lambtons will not die in their beds.”

On the way home and to the blacksmith, John Lambton had much to ponder. He didn't want to taint himself with murder, because even though it was an unpleasant prophecy, there was nothing like killing the first person who crossed his path. But the dragon had to be destroyed. Fortunately, as has been said, the Lambton heir was not only a skilled warrior.

The witch wasn't talking about humans. She said he had to kill the first one that greeted him.

By the time the blacksmith had prepared the required armor, it had already been arranged that at the sound of John's horn, the servants would unleash John's favorite dog. The poor beast would surely make its way to its master.

Having thus circumvented the terms of the curse, all that remained was to finish off the dragon. So John Lambton set out for the islet in the streams, and waited for the worm to return from its regular journey for a mouthful of milk, the dragon judged that two would not fit on so small a rock, and pounced on the knight.

It wrapped its body around him and was about to clamp down, which always worked, but alas, it impaled itself on the spikes. For the first time, non-human blood flowed. It evened out the forces, and after a brief struggle, the dragon's head fell into the flow of the River Wear under the blows of Lambton's sword. It was done.

Not really, John remembered as he waded ashore. He blew his horn to bring the whole story to a close with the death of an unsuspecting dog. And he set off for Lambton Hall.

He was horrified as he entered the exuberant castle, where everyone was celebrating the death of the dreaded monster.

No dog ran out to meet him. What's more, the first to run to his brave son was his delighted father.

The servants overheard the sound of the horn.

John Lambton would not be defiled by patricide. Quickly he blew the horn once more, and in a moment the dog rushed out, overtook the old gentleman, and the knight stabbed the animal. But it was too late.

Nine generations of Lambtons did not end up in their beds, the last of whom is said to have died crossing Brugeford Bridge.

Ilustration: Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

25.4.2025 (21.11.2004)